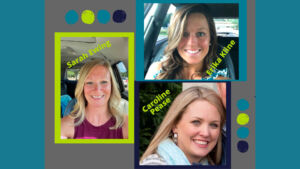

In September, I wrote a blog about how I became “a math person.” The whole time I was writing, I was happy to be telling the story I feel is important for people to hear, but I also recognized the fact I am not a current classroom teacher, and I am not teaching under current circumstances. Therefore, while my story might be eye-opening, perhaps it would be better to hear from others. In the blog I wrote that research tells us that when people of any age are pushed out of their comfort zone to learn something new, the neurons in our brain form stronger connections and these connections make us smarter. I believe that this notion, pushing me outside of my comfort zone, made me smarter at math and a lot better at teaching math. I’ve had the incredible opportunity to work with so many teachers over the years and am continually impressed with the hard work and dedication teachers put towards becoming better teachers – even in the most trying times. For this blog, I asked three teachers I’ve been able to work with in several different ways to share their story and offer words of inspiration to teachers who are just learning about ambitious math teaching and maybe feeling daunted by making any change in their classroom. I am here to tell you, I think you’d be hard-pressed to find many teachers who haven’t felt apprehensive about making changes. What is ambitious math teaching? An ambitious math teacher sees students as having the ability to make sense of problems and persevere in solving them. An ambitious teacher believes their students can make sense of new math ideas and use what they already know to solve problems. An ambitious math teacher’s voice is the secondary voice in the classroom – student voice is the primary voice. An ambitious math teacher allows kids to fail, acknowledges their mathematical thinking, and teaches them how they can learn from their mistakes. An ambitious math teacher encourages struggle because struggle can lead to great success (Huinker and Bill, 2017).  Caroline Pease, Sarah Ewing, and Erika Kline are all ambitious math teachers. They have attended countless professional development sessions over the years (and STILL are!) on how to become better teachers of mathematics. They’ve worked in various grade levels and taught through various district initiatives and policy mandates. They’ve taken baby steps in their classrooms to try new ideas they were apprehensive about only to see amazing results – the most important one being the pure joy children have about doing math. They are designated as math leaders in their districts and schools. With that, they all have struggled in their process, and each teacher needed to overcome feeling uncomfortable with change in order to find great success in their classroom. I had the most amazing conversation with all three of them. I wish I could just publish the transcripts; however, I can focus on common highlights here., My hope being they might be highlights that inspire teachers near and far to make shifts to ambitious math teaching – because the sheer joy of children learning math is a common theme among all three of them, and our goal here is for children to see they have amazing mathematical thinking and, indeed, are “math people.”

Caroline Pease, Sarah Ewing, and Erika Kline are all ambitious math teachers. They have attended countless professional development sessions over the years (and STILL are!) on how to become better teachers of mathematics. They’ve worked in various grade levels and taught through various district initiatives and policy mandates. They’ve taken baby steps in their classrooms to try new ideas they were apprehensive about only to see amazing results – the most important one being the pure joy children have about doing math. They are designated as math leaders in their districts and schools. With that, they all have struggled in their process, and each teacher needed to overcome feeling uncomfortable with change in order to find great success in their classroom. I had the most amazing conversation with all three of them. I wish I could just publish the transcripts; however, I can focus on common highlights here., My hope being they might be highlights that inspire teachers near and far to make shifts to ambitious math teaching – because the sheer joy of children learning math is a common theme among all three of them, and our goal here is for children to see they have amazing mathematical thinking and, indeed, are “math people.”

Your students’ experience as learners of mathematics doesn’t have to be the same as yours.

All three teachers talked about successes and struggles they had as students of math. Caroline and Sarah thrived off of sticker charts and timed tests, but do not utilize timed tests in their classrooms today. Caroline and Erika both had experiences in high school that turned them off of math almost completely. Caroline reminisced, “I always thought I was a strong mathematician, but high school made me really wonder if I was.” She remembered a day her math teacher said it was a review day and therefore there was to be no talking. She sat there and wondered how are you supposed to review if you can’t talk? Caroline and Erika lamented they struggled in some math classes because they didn’t know the why or the purpose behind the rules and steps they were given to solve problems or write proofs. Students in their classrooms today are constantly being asked questions like: “why did you do that?” “how did you solve that problem?”; and “tell me more about your mathematical thinking.”

Math can be a time of day that everyone in the classroom looks forward to.

All three teachers connected their favorite math memory to their own classrooms. They each talked about the joy and excitement children feel when they realize they have good ideas, their thinking is validated, or they make statements like, “I can do math!” I asked Erika Kline, “What happens when a child shares thinking you don’t understand?” She replied, “I just ask them to talk me through it and tell me why that works. In doing that, I’m validating their thinking. If I wanted them to see another way, I would show it to them or share another kid’s work to get them thinking about that too.” We talked about the need to develop a culture in your classroom where it’s ok to not know everything, and you may have to ask some questions to gather more information – and everyone is a part of that classroom culture, teacher included. Caroline shared her journey and where it is today, “ Math is my favorite time of the day. So many kids hate math. I want to be the one that helps them change their mind about math.”

An ambitious math teacher sees students as having the ability to make sense of problems and persevere in solving them. An ambitious teacher believes their students can make sense of new math ideas and use what they already know to solve problems.

The work we do is for students. We have to take risks for our students.

Caroline and Erika recalled how they once thought math was “black and white” and “rote.” They explained that the more they engaged in PD and tried new things in their classrooms, the more they realized how creative math actually is – that there’s not just one way to do things. Erika described her dilemma in realizing math was not going well in her classroom, “…and my kids didn’t like math. That made sense. I wasn’t enjoying it, so why would they enjoy it? I had to spend a lot of time figuring out myself as an educator. Once I figured this all out, I realized I had to do something different, and so I did. I had some PD on it and decided I might as well just try it. As soon as I did, it was SO COOL. All of the sudden, I was in their heads and could see what was going on in their brains.” Sarah described her journey beginning as soon as she started teaching. She was handed a scripted textbook and standards at the same time and realized the textbook was not addressing the standards in the way it needed to. She tackled this head on, and did so with confidence, realizing she needed to do something different for her students, “We adopted textbooks that were awful… they did not achieve the goal of test scores or children doing critical thinking. Fear comes from test scores. We need to think about life beyond the test score.” Sarah described a teaching career that has seen standard-based teaching, No Child Left Behind, standardized testing, and teacher evaluation changes. None of it has felt aligned, and her response has been to keep her eye on the ball – and the ball is the learning and critical thinking of children. And that is all.

Your biggest obstacle is yourself and the barriers you’re putting in the way.

Caroline described a main obstacle as being the fear of failure. She noted, “I think a lot of what started the fear of failure was the evaluation system. Knowing that if an administrator was in my room, and they saw that it wasn’t working, what they would think? So I really had to push through and think if I fail, I fail. I have to take risks for my kids. My kids are worth it. They hate math…so, it’s not about me and my failure. It’s about my kids and their success. It’s not about me and the evaluation system or what people think about me. It’s about the kids and how they change and how they have success.” Sarah eloquently described that sometimes a lesson can go poorly and turn out as a dumpster fire. Afterwards, you need to recoup and try again the next day. Others might see the dumpster fire and think, “I am also on fire and I should give up and go back to reading the script because I’m not good at this.” She reminds us, “You are not on fire. There are days that your math lessons will go badly. That’s just sometimes how math happens. We have 180 days…move on.” Erika explained that a lot of the barriers we subscribe to we have created in our heads. They are not real barriers. They are a result of the system in which we teach. We have the idea that we’ll get in trouble or be told no. These are created barriers. “We are the only ones who can do something about those barriers. No one is going to come to your classroom and save you from what you’re doing. You’ve got to do it yourself.”

Grab a colleague to join you in taking baby steps.

Caroline, Sarah, and Erika explained they didn’t do any of this alone. They had someone supporting them and/or working side by side with them. Instructional coaches are called upon, teammates are asked to dabble in new ideas and serve as sounding boards and encouraging colleagues. A simple conversation can make everything feel less overwhelming and build confidence. No matter what, start slow. Try one thing. Ask one question. In doing this, your kids’ work and their attitude towards math will show you how it’s going. On her famous Tedx Houston talk, Brene Brown describes herself as, “…straddling the tension between leaning into the discomfort and finding refuge in my old friends, prediction, and control…Truthfully, I had no idea what I was getting into” (Brown, 2012, p. 13). When we try something new, we have no idea what we’re getting into. We can attend countless PDs, watch someone do a model lesson for us or watch another teacher teach to get a feel for what it should look like. We can read all the books and articles and really know the content, but we simply have no idea how it’s actually going to unfold in our classrooms. When I read this passage in Daring Greatly, I likened “old friends” to teaching rules, procedures, and tips and tricks. It can just feel easy and more comfortable. However, upon reflection, rules, procedures, and tips and tricks are not “friends.” I was taught rules, procedures, and tips and tricks and had no connection or fondness towards math. It was not my friend. So why is it, when we feel lost or overwhelmed, we lean on things that didn’t work for most of us in mathematics? Therefore, like Caroline, Sarah, and Erika describe above, we need to lean into the discomfort. By tackling the discomfort with baby steps and small moves, ultimately, you will find yourself an ambitious math teacher guiding children to becoming critical thinkers and ready to tackle the math they will encounter for years to come. They will make sense of problems and persevere in solving them. They will ask questions, debate, and learn from their mistakes. They will recognize the amazing benefits of productive struggle. Most importantly, they will find joy in learning math, and they might even consider themselves, “math people.”

Resources

Please login or register to claim PGPs.

Alternatively, you may use the PGP Request Form if you prefer to not register an account.