As you’re likely well aware, sleep is mediated by a number of important factors: metabolism, temperature, stress, etc.

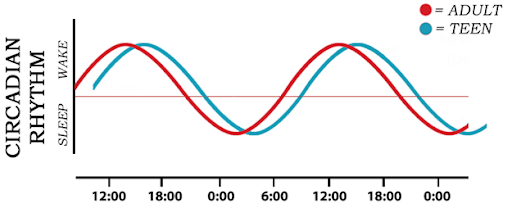

The most powerful driver of sleep, however, is the sleep/wake circadian rhythm. Within human beings, this 24-hour cycle is largely mediated by the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus: a tiny brain region that receives direct input from the eyes and is highly responsive to sunlight. Amongst adults, this ‘master clock’ typically triggers sleepiness around 9pm, deep sleep around 2am, and wakefulness around 6am.

Here’s the fun bit: during adolescence in practically every animal we have ever studied – from rats to birds to fish – this circadian rhythm shifts. Within human beings, this shift manifests as a two-hour delay. This means, for teenagers, sleepiness is triggered around 11pm, deep sleep around 4am, and wakefulness around 8am.

Although the precise biological mechanisms for this phase-shift remain unclear, likely drivers include puberty hormones and neuronal pruning. More interesting than the mechanistic question, however, is the behavioral question: why would all animals change their sleep pattern during adolescence?

A prevailing theory concerns learning. Amongst most animals, the young are protected and cared for by adults. However, come puberty, protection is withdrawn and adolescents must enter the competitive world of adults. Food, mates, shelter: everything is up for grabs and juvenile creatures almost certainly won’t be able to outcompete more experienced adults. For this reason, it’s believed adolescents carve out a unique ‘social niche’ during which time all adults (and children) are asleep and removed from the picture. Theoretically, this allows them to practice and hone cooperative and competitive strategies with others on equal footing.

Though an adolescent sleep-shift is beneficial to many animals, it can prove quite the hindrance to human teenagers. With the constraints of school, not only are many teenagers not fully awake for morning class, but they also accumulate ‘sleep debt’ throughout the week (losing between 1-3 hours of sleep per weeknight). Naturally, many teenagers try to make-up for this debt by sleeping in on the weekend – unfortunately, this only serves to push the circadian rhythm even further out of sync. By the end of a semester, some teenagers might not feel sleepy until well after midnight and won’t feel awake until nearly noon.

How can we help? I suppose we could start school later. In fact, some research suggests later school starts can impact mental health and academic achievement. Unfortunately, schools are run by adults. Asking teachers to start their day 2 hours later would mean many wouldn’t leave campus until 7pm or later. Outside of boarding scenarios, I don’t reckon this is viable.

The key, then, lies in routine. The more teenagers have sleep (and larger life) routines, the better chance they have of diminishing sleep-shift impacts. Turning off technology, stopping homework, and dimming lights at the same time each evening can externally trigger the sleep cycle. In addition, exercise, diet, and consistent pre-bed behaviors (meditation, stretching, reading) can further override the sleep shift. Finally, avoiding naps and maintaining the same wake/sleep routines on the weekend are key as well.

Occasionally, things can go haywire. For example, I have a nephew who recently dropped out of high school and is currently stuck in the ‘game all night, sleep all day’ cycle. In these instances, a very strict sleep/wake routine supplemented by light therapy (which aims to mimic sunlight and ‘trick’ the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus) and pharmaceuticals may be required. Though, it’s best to save the heavy artillery until after all behavioral and environmental strategies have been exhausted.

This leaves open the question – what impact does this phase-shift have on student learning and memory?

“Every human being requires at least 5 sleep-cycles per night to maintain optimal health, function, and memory – which equates to ~7.5hrs of sleep.”

To help understand, here is a short video outlining relevant considerations:

The title of this post asks, “How much sleep do teenagers really need?” The ultimate answer might be both frustrating and trite: teenagers need the same amount of sleep as everyone else (perhaps even a bit more during periods of bodily growth spurts). Every human being requires at least 5 sleep-cycles per night to maintain optimal health, function, and memory – which equates to ~7.5hrs of sleep. Once we account for between-cycle periods (where we might use the restroom or get a glass of water), an 8- or 9-hour night will suffice.

Many teenagers argue that they can thrive off far less sleep: say 4-5 hours a night. The good news: there is a subset of people (called natural short sleepers) who appear to be able to do this effectively. The bad news: only 50 families with this genetic variant have ever been identified. This means far, far less than 1% of the human population can seriously claim this ability – and your teenager is not one of them. Outside of these 50 families, the percentage of people who can demonstrate strong cognitive performance following only 5 hours of sleep is zero.

“Sleep is as much a part of the human memory and learning process as any pedagogy, study technique, or revision strategy students may employ.”

In the end, when we think of schools and learning, sleep is often a rare consideration. However, sleep is as much a part of the human memory and learning process as any pedagogy, study technique, or revision strategy students may employ. Accordingly, it’s important that both kids and their parents (who will largely drive sleep patterns at home) understand these key mechanisms and influences of stress.

Resources

Please login or register to claim PGPs.

Alternatively, you may use the PGP Request Form if you prefer to not register an account.