In education, like many other fields, context matters.

Galileo Newton

Hooke Faraday

Curie Einstein

Swan Leavitt

Meitner Franklin

In physics, context matters a lot. The folks listed above discovered new contexts or paradigms in the natural world using the tools they developed as physicists and astronomers. Each of these new contexts radically and profoundly changed our society, for better or worse.

Galileo Galilei (1564 – 1642) showed the power of the scientific method over blind adherence to authority. His discoveries and media blitz across Europe ushered in the contexts we call Heliocentrism and modern science. These brand new contexts so offended Europe’s primary authority, the Catholic Church, he spent his final days under house arrest. Issac Newton (1642 – 1727) used the free time afforded to him during his home-quarantine (sound familiar?) during the Black Plague to [arguably] invent calculus. He also formalized the science of optics and physics through experimentation and mathematics. These new contexts made it possible to do stuff with math – like build bridges, send rockets to the moon, and make cars go. Robert Hooke (1635 – 1703) discovered the cell and microorganisms, using the new fangled compound microscope. This new context taught us that big things are made of small things! This new context opened the door for the germ theory of disease and much of biology Michael Faraday (1791 – 1867) worked in the 1820s and 30s to deepen scientific understanding of and formalize the science of electromagnetism. He was among the first to realize Newton’s F = ma could not describe electricity and magnetism at all. The new context he discovered, electromagnetic induction, directly led to the Industrial Revolution. Marie Curie (1867 – 1934) discovered Radium and properties of radiation and radioactive agents. Curie is still the only person with two Nobel Prizes in scientific fields, one in Chemistry and one in Physics. This new context laid the groundwork for chemotherapy, nuclear power, and nuclear weapons. Albert Einstein (1879 – 1955) proposed two new contexts, the quantum nature of light and the phenomena of relativity. Quantum and relativistic physics, studied and formalized by many people, not just Einstein, made our modern era of technology possible, from computers and iPhones to GPS. Henrietta Swan Leavitt (1868 – 1921) discovered stars called Cepheid (seh-fi-id) variable stars. These stars can be used to find distances to celestial objects. Her work led directly to the discoveries that our universe is expanding and that our galaxy is just one of billions and billions of galaxies. Lise Meitner (1878 – 1968) discovered Nuclear Fission, the process which made nuclear power and the atomic bomb possible. This new context changed how wars are fought (or not fought) and changed the geopolitical stage irreversibly. Rosalind Franklin (1920-1958) took the first “picture of DNA” using x-ray crystallography, our first look at how DNA is structured. The context of the genetic revolution has changed our lives in many ways from criminal justice to home kits which can tell you your ancestry.

Though this is not an exhaustive list, like I said – context matters. When physicists discover a new context, some realm of our universe we didn’t even know we didn’t know about, is uncovered. When I was a classroom teacher I crammed as much context into my lessons as I could, trying to paint a picture of who does science, and what context allowed them to change the world. Besides being personally interesting to me, it hooks students with the humanity of how science is done. Obvious questions like “why did they lock Galileo up?” or “Didn’t Watson and Crick get credit for discovering DNA?” or “Why have I never heard of Henrietta Swan Leavitt?” makes the lesson come alive. So I beseech you fellow educators, give your students the context they need to learn and grow.

“give your students the context they need to learn and grow”

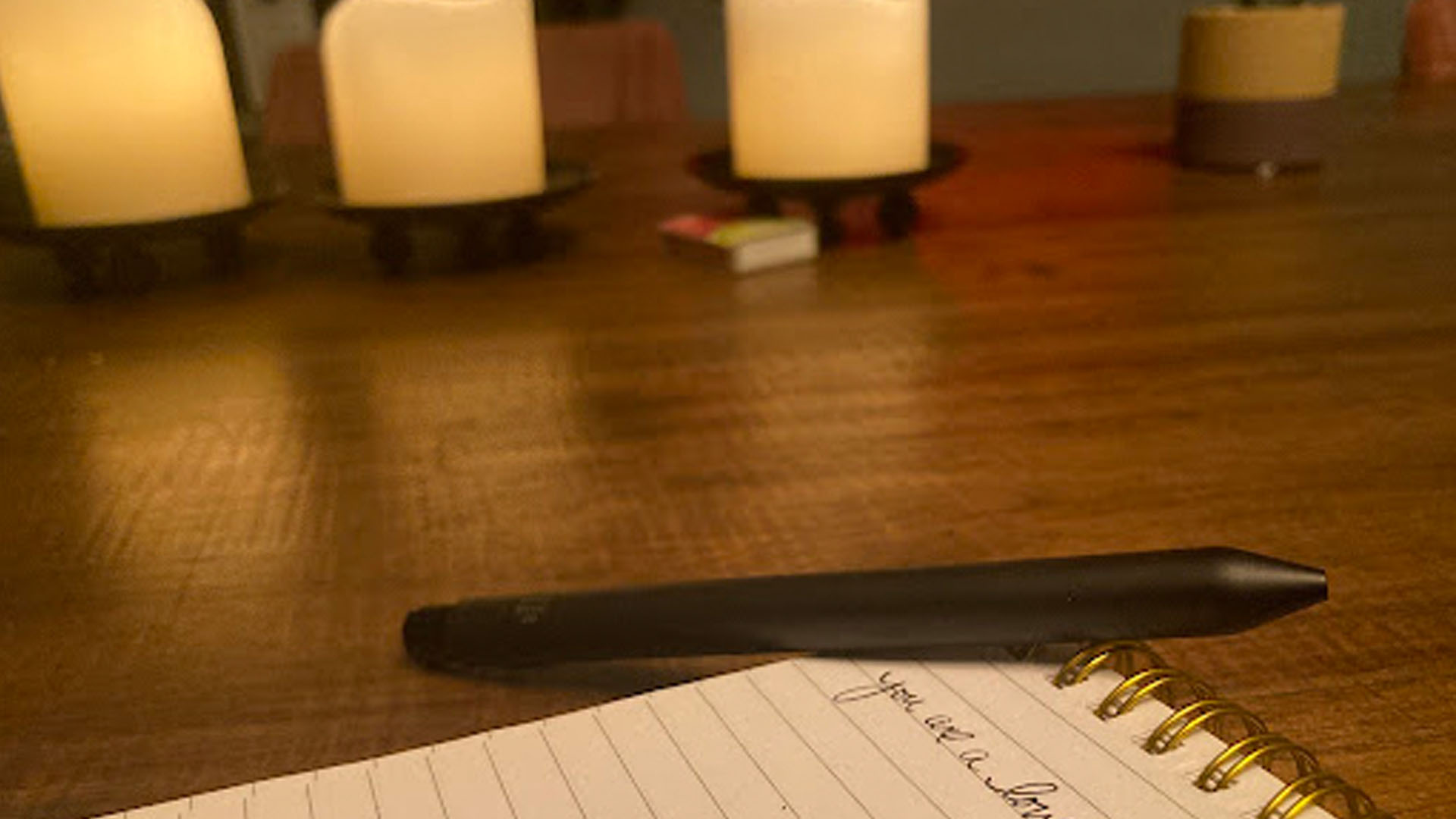

And now some further context… I was a Physics and STEM teacher for 8.5 years before systemic and personal challenges forced me to leave the classroom to take care of my mental health. While I was in the classroom, my lesson plans satisfied my creative itch in a way I did not realize until I left. Leaving the classroom showed me I needed to heal, and making art has been a big part of that healing journey. I’ve honed in on photography as a creative outlet; it’s just about as close as art gets to being straight-up applied physics. Context matters in photography as well. When I took this photograph, all I knew were the following three keys:

- You should control how much light you allow into your camera (or in this case, iPhone).

- You should really try to make the subject and other objects meaningful in some way.

- And finally you should make sure the subject is in focus.

The reason I say context matters is as you decide the above 3 keys, what you want your photograph to say will require you to make decisions about light, subject, and focus. I honestly didn’t know what I wanted to say when I set up this shot in my living room. I knew that I wanted to make my subject the words on the paper, so those should be in focus. Beyond that I grabbed objects from around the living room, so it was not hard to make personal meaning with them. What’s been astonishing is how folks have reacted to me showing them this photograph. I’ve done the quite unusual thing and printed this photograph to show to complete strangers. I’ve probably shown this picture to more than 50 strangers just to get their reaction. People bring their own context to experiencing this photograph. Some people are silent, taken by the emotion of the scene. Some begin to notice the composition of the photograph, commenting on the tone and balance of the shot. Still others seem perhaps not sure of their art appreciation bona fides and ask questions like “so what am I supposed to do now?” Importantly, everyone eventually turns the photo at a slight angle (or tilts their head) and reads those words, “you are a lovely soul”. That turned out to be what I wanted to say.

Context in the Classroom… I started thinking about context after listening to Malcolm Gladwell’s excellent audiobook, Talking with Strangers. It should be required listening (Gladwell recommends listening instead of reading and I agree!) for all teachers. I wanted to see if what Gladwell suggests is correct – he proposes that the key to talking to strangers is context. In fact, the words, “you are a lovely soul” were written by a stranger. After I had been fired without warning and without explanation from a camera shop gig, I was a mess. I spilled my context about losing my job and questioning everything all over the employees at my favorite shop. I’d gone in for a little retail therapy and a kind employee clocked out to help me get the supplies I needed. Providing her with my context both helped her guide me to the journals and stickers I needed, and helped her see into who I am. She didn’t ask to change my life, but on that day, her writing “you are a lovely soul” with the pen pictured in the image, made me weep. It halted my descent into questioning everything and allowed me to begin the hard work of starting over again. When a stranger gets a chance to see your true and honest context, incredible things happen. My fellow educators, please consider your students’ context. You should ask them about it. They will tell you about it if you do. You can do this by making one tiny adjustment to your teaching practice. Ask each student how they are doing. Every. Day. The way I did that was by making the first question on bellwork something like “What’s one thing or person you feel grateful for today?” or “What’s something you’re looking forward to?” or “What’s something you’re frustrated by” or “what’s something you’re proud of?”… and on and on. You can even recycle these questions on a fairly short basis – because the context for each student changes everyday. Example bellwork from an Earth Science Class You’re smart so I won’t tell you what to do with the bellwork, or if you should discuss the answers, you know the context of your classroom better than I ever could. I can tell you the teachers who I saw implement this alongside me build deep and complex relationships with their students. These are the relationships you must build to get a student who doesn’t know when their next meal will be to try to solve a two-step equation. Or to get that 5 page term paper handed in on time. During my time in the classroom and stint as experimentalist trying to see if context really is as important as Malcolm Gladwell suggests – has shown me that when context is absent, conflict often arises. However, when the context is clear to all involved, incredible things can happen between strangers.

Resources

Please login or register to claim PGPs.

Alternatively, you may use the PGP Request Form if you prefer to not register an account.