While headlines focus on policy changes and budget cuts, the school year is already in full swing in Indiana. Through overbearing uncertainty, creating a sense of belonging in schools and classrooms every day is both more challenging and more essential.

As we learned in The Opportunity Makers, trajectory-changing schools create an emotional climate for learning that activates students’ ability to excel. We’re committed to supporting educators as they build a full understanding of each student to meet their needs and support their long-term growth. We hope the stories and practices shared below support all school-based staff to create an environment of educational belonging for each student.

“Belonging takes more than warm relationships. It is created by intentional policies, practices, and systems that respect students’ identities, recognize their agency, and affirm their ability to succeed.”

Research Foundation

Belonging—the experience of being accepted and respected—is a prerequisite for learning. Belonging takes more than warm relationships. It is created by intentional policies, practices, and systems that respect students’ identities, recognize their agency, and affirm their ability to succeed. Trajectory-changing schools foster belonging in three interrelated ways:

- Individual Knowledge: Every student is known well as an individual and a learner. This explicit expectation is modeled by teachers and leaders and reinforced by school structures.

- Individual Needs: Educators work together to identify needs and provide personal support which are discussed collectively and acted on consistently.

- Individual Growth: Educators focus on incremental growth for every student over time. They set long-term learning goals, use individual student data to tailor support, and celebrate progress.

Belonging is not separate from rigorous academics; care and challenge go hand in hand. The whole institution must work to understand the experiences of individual young people—not just because it’s right, but because it’s the best way to build on students’ gifts and boost their learning.

For this generation of students, who’ve had minor and major disruptions in learning, who struggle with strong attendance and experience mental health challenges at a higher rate than previous generations, school must be a place where they experience both care and challenge.

“School must be a place where they experience both care and challenge.”

Stories in Action

One of the major myths we found in doing this research is the idea that simply having strong, warm relationships with students is enough to build belonging. While it’s true that individual relationships are important for student well-being, we see examples across many classrooms where despite strong relationships with a caring adult, children are at risk of not meeting their potential or irreparably falling behind in their learning. We must go beyond our traditional understanding of belonging so school teams can spend time on practices that proactively lead to real safety, acceptance, community, and ultimately, belonging.

One of the major myths we found in doing this research is the idea that simply having strong, warm relationships with students is enough to build belonging. While it’s true that individual relationships are important for student well-being, we see examples across many classrooms where despite strong relationships with a caring adult, children are at risk of not meeting their potential or irreparably falling behind in their learning. We must go beyond our traditional understanding of belonging so school teams can spend time on practices that proactively lead to real safety, acceptance, community, and ultimately, belonging.

You can read more stories on the practices schools used to build the kind of belonging that leads to trajectory-changing experiences for students in our full research paper, The Opportunity Makers.

Tools to Use

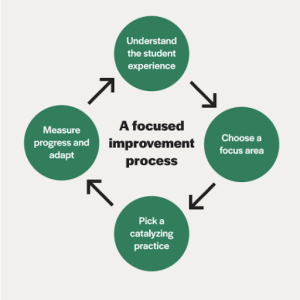

Rather than launching one-off initiatives, we encourage school leaders to start an ongoing improvement cycle that leads to sustained change. In our research, we repeatedly witnessed schools using a four-part improvement cycle to build trajectory-changing practices and schools:

1. Assess the students’ experience of belonging

Schools should work to understand how students experience belonging at school. We suggest collecting student input with student surveys and focus groups. From there, schools can identify areas for growth.

In The Opportunity Makers, young people at all schools tended to report that they trusted their teachers, but students at trajectory-changing schools were more likely to feel supported by their school. It is important that schools investigate belonging at both the teacher and school level. To begin, schools can ask the four student survey items used in The Opportunity Makers.

- I feel supported by my school;

- People at my school care about me;

- When I feel like giving up, my teacher asks me to keep trying; and

- My teachers make me feel like I belong.

2. Choose a focus area

Individual knowledge, needs, and growth all build on each other. Schools should start by developing individual knowledge of students if that’s not already in place. From there, schools can use that knowledge to better support needs and boost growth

If you haven’t yet, consider taking TNTP’s Baseline Assessment about your school’s trajectory changing practices. You can use the assessment data and student input from the student survey to reflect on how existing school policies and practices enhance or detract from belonging.

Note the strengths and gaps in individual knowledge, needs, and growth. We suggest these reflection questions:

- Individual knowledge: What shifts in practice will break down siloes of information about students across the school?

- Individual needs: How do our structures for collecting and sharing knowledge of student characteristics and academic needs reinforce collective action?

- Individual growth: How is the focus on growth over time reinforced (or reduced) with our cycle’s progress monitoring?

You can then use these reflections to select an initial school-wide focus for belonging. When in doubt, invest first in individual knowledge and build to the other areas.

Once you know your focus area, communicate your school’s priorities for belonging. Schools should set an explicit goal to build belonging and an emotional climate for learning. Communicate these priorities for belonging to the rest of your school stakeholders and ecosystem. You can share areas of strength and growth based on students’ input and assessment of current practices, key reflections from your school team, and how you intend to build belonging.

3. Pick a catalyzing practice

There are several practices that reinforce the focus areas above, along with tools adapted from trajectory-changing schools. We recommend adopting one or two practices at a time and using them consistently to build new habits.

Individual Knowledge Catalyzing Practice: Map existing relationships with students.

Every student should be known well by at least one adult. To assess existing relationships with students, write all student names on chart paper and ask staff members to put a check mark next to students with whom they have a genuine relationship. Note which students have no advocates, and brainstorm ways to reach them.

Resource: Relationship Mapping Protocol (TNTP)

Individual Needs Catalyzing Practice: Create comprehensive student profiles.

Knowledge about each student should be centrally documented so that the information builds from year to year. Student profiles can include academic data, language data, strengths and areas of growth, interests, individualized plans that help contextualize data (e.g., Individual Education Plans, Language Plans, Behavior Plans), and familial and cultural context. Teachers can use the profiles to have regular conversations about shifts in personal or academic factors and document next steps for support. They can share the profiles with incoming teachers, so the knowledge builds from year to year.

Resource: Creating Comprehensive Student Profiles (TNTP)

Individual Growth Catalyzing Practice: Choose and use a long-term growth metric.

Each student should have a challenging yet reasonable goal that puts them on track for reaching grade level over time. Some students won’t catch up in a single year—and that’s OK. Instead, trajectory-changing schools break down the big goal into small chunks and constantly celebrate progress with students and all stakeholders. This focus on growth affirms students’ capacity to succeed. Young people believe in their capacity to meet their goals because everyone around them believes it too.

Assess school context.

The growth metric should align with the school’s long-term goal for students, respond to the community’s needs, and serve as a powerful tool for motivation and accountability. Use historical data to determine where students have displayed excellence or encountered challenges.

- Example: Educators at Van Buskirk Elementary believe that literacy is the door to building critical thinking skills and accessing grade-level content in any subject. They focus on every student reading on or above grade level by middle school.

Pick a metric.

Choose a metric that aligns with the overall goal and resonates with the school community. This could be quarterly or state testing or something specific to the school, like progress on a reading program. The metric should reinforce the school-wide focus rather than operate as a compliance metric for the sake of reporting.

- Examples: (1) Students will achieve 1.25 years growth in reading as determined by our readiness assessment; or (2) students will score “proficient” on weekly math formative assessments.

4. Set individual student goals.

Using the metric you’ve chosen, teachers should work with students and families to set long-term growth goals for each individual student, along with clear benchmarks for progress. These goals should be challenging yet attainable.

- Example: Reading goals for bilingual students could include biliteracy trajectories (the developmental paths they follow in acquiring literacy skills in two languages).

Resource: Summative Assessment Data Reflection Guide, adapted from CE Rose PK–8

5. Measure progress and adapt

Schools should start small, monitor their progress, and adapt as they go. They can lean into practices that work and drop the ones that don’t. As one focus area is woven into the fabric of the school, leaders can pick another and start the cycle over again.

The Bigger Picture

The 1,300 schools we studied in The Opportunity Makers prove that US public schools can change the academic trajectories of millions of young people who’ve fallen behind. We’re so excited to share the promising practices these schools lean into every day, to support more educators in building the systems and environments our students all need to thrive. We’re especially excited to hear your questions and stories from the field, so please take 3 minutes or less to share your thoughts on our survey here.

Resources

- Immordino-Yang, M. H., Darling-Hammond, L., & Krone, C. R. (2019). Nurturing Nature: How Brain Development Is Inherently Social and Emotional, and What This Means for Education. Educational Psychologist, 54(3), 185–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2019.1633924

- Felten, P., & Lambert, L. M. (2020). Structures for belonging: A synthesis of research on belonging and a framework for student success. Student Experience Network. Retrieved from https://studentexperiencenetwork.org/wpcontent/uploads/2021/03/Structures-for-Belonging.pdf

- Hammond, Z. L. (2015). Culturally responsive teaching and the brain. Corwin Press

- https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2025/03/250311154056.htm

Please login or register to claim PGPs.

Alternatively, you may use the PGP Request Form if you prefer to not register an account.