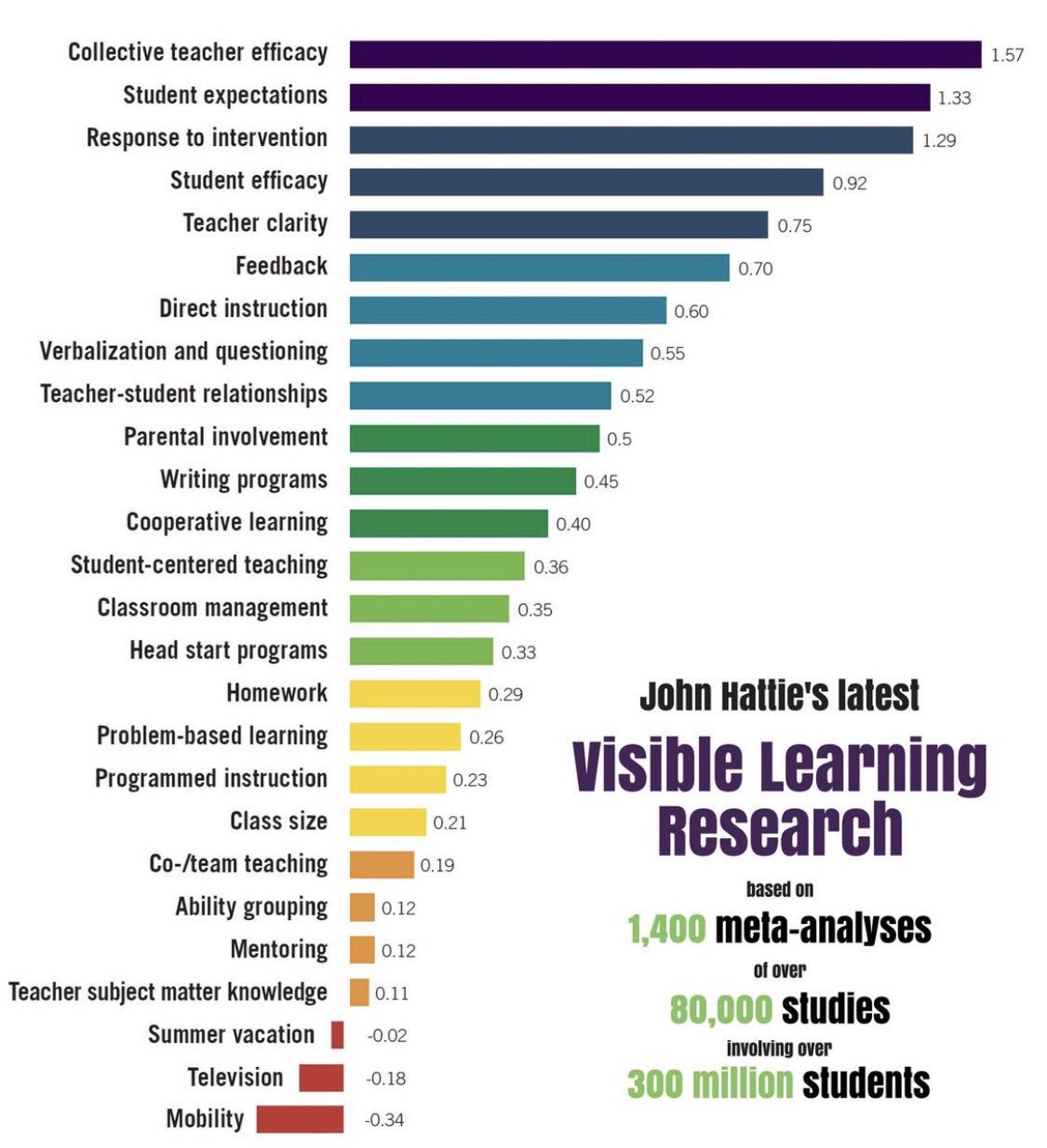

Stop for a moment and ask yourself this question: When was the last time I took a risk? How you choose to define risk is entirely up to you, but I would venture to say that each of us has varying connotations of the meaning of the word. By definition, a risk is something that creates peril, danger, hazard, or jeopardy. By implementation, risk-taking is the crucial element needed for personal and professional growth. A risk requires a step—and sometimes a leap—into something new, different, and unpredictable. If we’re going to make an impact on the lives of our students (and each other), I’d say it’s about time we got comfortable with the unpredictable. Teaching, by nature, feels like an erratic profession where new, innovative ideas are applied to address long-standing, predictable concerns. When a student arrives in our school several years below grade level reading standards, we are concerned but in a predictable, “We’ve dealt with this need before” kind of way. When a freshman arrives at her algebra class without a basic sense of math facts, we are frustrated though unsurprised by this gap in her skill set. There is a pervasive paradox between anticipating the needs of our students and knowing how to best respond. The primary purpose of our profession is to meet the learning needs of our students. Learning needs can occur in academic, behavioral, and emotional lessons, but the fact remains that our job is to teach what our students need to learn. So, why then, if we can readily predict the needs of our students, do we still stumble over how to reach the students who need us the most? Why does it seem so difficult, so daunting, to think of the next right strategy to try with our students? The answer may upset you. For too long, we have functioned in a profession where autonomy and gut instinct has paved the way for educational decisions. It wasn’t until 2009 when John Hattie first published the world’s largest meta-analysis of influences on learning, did the education field even have a systematic way of determining what does and does not work in our profession. Sure, we had our experiences to fall back on, but considering the fact that there are literally millions of teachers with varying experiences around the world—it’s safe to say that spotting what works is difficult to do on our own. Hattie’s research, referred to as Visible Learning, sheds much-needed light on answers to age-old questions such as:

- “To what extent do anxiety and depression impact learning?”

- “Should phonics be taught directly?”

For the past decade, publication after publication has clarified what we should do with the research found in Hattie’s ongoing meta-analysis, but where is the translation to teacher-preparation programs, classrooms, and districts? Why are we still reacting to predictable learning needs with impulsive teaching strategies that may or may not actually help students? If the trend in our profession has been to throw a smattering of solutions at predictable concerns—then the risky decision is to teach and lead with clarity and precision. It’s time for the guessing game to end.

Image found here.

Hattie’s research is clear: Collective Teacher Efficacy and Teacher Estimates of Achievement are the top two influences on student learning in our world today. Following close behind are Student Expectations of Learning, Response to Intervention, Teacher Clarity, and Student Efficacy. Notice a trend? Beliefs, more than actions, systems, or strategies, make the difference. Efficacy is the belief that you have worth. That you have the power to make a difference or cause an impact. When teachers and students believe they matter—research shows that gains in learning are high. So where’s the risk in this research? Well, for starters, we need to stop believing that the real answers are just around the corner—out there—away from schools, classrooms, or teachers. We need to stop all rhetoric that pits educators against themselves or students, and we need to center our mission on what is proven to be the truest: teachers who believe their efforts, together, make the difference–have the highest impact on student learning. To say we have control over the situation feels risky and unpredictable. Ours is a field of study built on people, and people are filled with variables and emotions. To proclaim that despite these variances, we, the teachers, still have the ultimate influence on learning—well, that’s a bold statement we need to make again and again. Until we believe it. For more about John Hattie’s research, take a look at what Laurie learned at the Visible Learning Conference.

Resources

Please login or register to claim PGPs.

Alternatively, you may use the PGP Request Form if you prefer to not register an account.